My Casino Background 2: Playing Blackjack for a PhD

Post 2 of 2 about my background with casino gambling and decision science

This is a long-overdue follow up to the previous newsletter describing my background in casino blackjack both as a hobbyist (Part 1) and later as a researcher (Part 2, this newsletter). That experience and research provides most of the data and inspiration for the upcoming newsletters in this Substack. This is a long post meant to get relevant but somewhat boring and navel-gazing background out of the way, but without the kind of useful, fun, or thought-provoking content that I intend for future posts. With that in mind, don’t hesitate to skip or skim. Here are links to the newsletter sections with brief descriptions to make skimming easier:

Cultural Psychology (what is it and why do I care about it)

The Psychology of Judgment and Decision Making (what is it and why do I care about it)

The Gambling Metaphor and Its Critics (the importance of the gambling metaphor to how scholars understand decision making under risk and uncertainty, and a consideration of important criticisms)

Playing Blackjack for a PhD (describes my specific dissertation research project, including a brief summary of methods)

Cultural Psychology

My experience as a card counter in casino blackjack described in the previous post became relevant in graduate school. Several years after I had stopped counting cards. I was accepted into the interdisciplinary PhD program the Committee on Human Development at the University of Chicago. The Committee’s flagship areas of specialization were the closely related fields of psychological anthropology and cultural psychology (the main difference being their respective affinity to the fields of anthropology and psychology). I tended toward the more psychological side. Both disciplines emphasize the interdependence of culture (the unique distribution of practices, values, beliefs, and designed environments shared by a group) and psychology (mental processes impacting how people think, feel, judge, perceive, decide, and behave). I fell in love with cultural psychology and the many lessons it had to share about human behavior and cognition.

For some thought-provoking and accessible popular scientific books on the topic see Richard Nisbett’s (2003) The Geography of Thought (though there are good reasons to be skeptical of his origin story and the related East-West geographical divide), Nisbett and Dov Cohen’s (1996) Culture of Honor (a great example of compelling social psychology research and theory designed to establish the long-lasting impact of historical culture and geography on cognition), Joseph Henrich’s (2020) The Weirdest People in the World (though I am skeptical of his central thesis that Westerners are distinctly unique relative to other cultural groups for reasons described here), or Malcolm Gladwell’s Outliers (my favorite of the bunch, despite the book being written by a journalist rather than a scientist and not explicitly framed as a cultural psychology book).

The Psychology of Judgment and Decision Making

For my PhD dissertation research, I focused on the psychology of judgment and decision making (J/DM), which has broad overlap with the economics subdiscipline of behavioral economics. Much of the research in this field begins with normative (optimizing) models of rationality and explains deviations from those normative models with reference to mostly inbuilt, species-general cognitive heuristics (such as the availability and representativeness heuristics) and resulting biases (any systematic deviation from the dictates of rational choice). This is thanks, in no small part, to the pioneering work of the late Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman, although there is a much longer list of eminent scientists who have been foundational to the field, including a handful of Nobel laureates in economics. Kahneman (a Nobel laureate himself) sadly passed away on March 27th of this year. The emphasis on heuristics and biases has provided an important rejoinder to assumptions in classical economics that the accepted models of rational choice were not just normative but were also descriptive: they were taken not just as good models for how rational people ought to choose, but also as the best models we have to capture how people actually choose. Kahneman and Tversky, along with many other scholars, have convincingly demonstrated that these models do not capture how people make choices. Instead, they argue, inbuilt cognitive processes—most often rules of thumb called heuristics that usually work but that also lead to systematic and predictable errors—explain systematic deviations from these normative models.

Some of the fun (but also controversial) examples of this research concern what Kahneman and Tversky call the Representativeness Heuristic which is associated with a range of systematic errors or biases including, the base rate fallacy, the law of small numbers, the conjunction fallacy, and the hot-hand cognitive illusion.

The Gambling Metaphor and Its Critics

Models of heuristics and biases, and of decision processes more generally, have been strongly influenced by gambling as a metaphor (a) for how all decisions under risk and uncertainty ought to be made (normative models), such as utility theory (b) for assessing irrationality or bias with respect to how judgments and decisions are in fact made (descriptive models), and (c) for the design of research stimuli used to develop those descriptive models (for a rich and critical discussion of this approach, see Goldstein & Weber, 1995). The gambling metaphor has been used to describe risky or uncertain decisions far beyond the gambling domain to cases where choice options, probabilities, outcomes, and the associated costs and benefits of those outcomes are often poorly understood and play an ambiguous role in how people make decisions. Here’s a nice justification for the use of the gambling metaphor to create experimental stimuli from none other than Kahneman and Tversky, from their 1984 paper, “Choices, values, and frames” (p. 341):

Risky choices, such as whether or not to take an umbrella and whether or not to go to war, are made without advance knowledge of their consequences. Because the consequences of such actions depend on uncertain events such as the weather or the opponent’s resolve, the choice of an act may be construed as the acceptance of a gamble that can yield various outcomes with different probabilities. It is therefore natural that the study of decision making under risk has focused on choices between simple gambles with monetary outcomes and specified probabilities, in the hope that these simple problems will reveal basic attitudes toward risk and value.

To those long-trained in decision science, or anyone reading this essay who has inevitably been exposed to the analogy between life and gambling, it may seem to follow as a matter of course—to be “natural” as Kahneman and Tversky wrote—that risky or uncertain decisions can be understood as choices among gambles. But for those who have not been repeatedly exposed to the gambling metaphor, I suspect risky and uncertain decisions could just as convincingly have been framed in very different ways. After all, outside the domain of many popular games of chance, we usually have unreliable and ill-formed opinions about (a) the range of possible choices, (b) the possible outcomes that might arise from those choices, (c) the probabilities of those various possible outcomes (which themselves may vary widely across time depending on contextual changes), or (d) the utility that each of those potential outcomes might have for us. Given the radical uncertainty that obtains for even banal choices (“whether or not to take an umbrella”), not to mention for the really important decisions (“whether or not to go to war”), the idea that rational decision makers should frame risky or uncertain choices like gambles might seem just plain WEIRD (see the below section on comparative methods to make sense of this intentional pun).

One convincing criticism of the gambling metaphor comes from Goldstein and Weber’s (1995) paper, “Content and discontent: Indications and implications of domain specificity in preferential decision making.” They make a compelling case that the use of the metaphor, among other content-impoverished norms in cognitive psychology, may systematically misrepresent cognitive processes. As the write (p. 92):

The point is not merely that the experimental practice of using content-impoverished stimuli would have failed to discover a number of interesting phenomena, but that the particular phenomena that would have been overlooked are those that conflict with the overarching theoretical framework.

They point to a range of research suggesting that when researchers consider real-world decisions that are embued with meaning, it turns out that the meaning (the content) plays an important role in the cognitive processes. For a compelling experimental example in decision science, see Medin et al.’s, “The semantic side of decision making” (1999).

A second critical approach challenges the idea that the received normative models of rational choice are in fact normative. This criticism originates with the pioneering work of Herbert Simon (another Nobel Laureate) on bounded rationality. That work—without drawing a sharp line between normative and descriptive models of choice—argues that classic models of rationality make unrealistic assumptions about available time, information, and information processing capacity. Instead, Simon argued that models of rationality should be based on more realistic models of human cognition that take into account such limitations. Simon proposed heuristics as an example. For examples of Simon’s classic work on bounded rationality and heuristics see his classic essays, “A behavioral model of rational choice” (1955; introducing the idea of bounded rationality) or “Rational choice and the structure of the environment” (1956; introducing heuristics, and in particular satisficing, as a boundedly rational alternative to unrealistic classical models of rational choice).

Simon’s work was not critical of the heuristics and biases tradition—Simon has in fact praised that work—rather, it preceded and helped justify Kahneman, Tversky, and their colleagues’ separation of normative and descriptive processes; their emphasis on heuristics as an alternative to optimizing normative models of choice; and their findings that people’s choices systematically deviate from the predictions of normative models. But many contemporary scholars have referred back to Simon’s work to point out that the normative status of those models is also problematic and, therefore, to question the readiness to attribute deviations from those normative standards to bias or irrationality. The most persistent and often compelling criticisms come from Gerd Gigerenzer and his colleagues with work on smart heuristics (see for example, the books Simple Heuristics That Make Us Smart, Bounded Rationality: The Adaptive Toolbox, Ecological Rationality: Intelligence in the World)

My training and interest in cultural psychology fit well with both criticisms, convincing me that the gambling metaphor was ill-suited for either understanding or evaluating decision making under risk and uncertainty. I believed—and still do—that culture; culture-specific built environments within which humans spend an increasingly signification portion of their time (including casinos); and individual and social learning within those environments together play a far more proximal and illuminating role in both how—and how well—people make decisions than the current body of research—with its emphasis on domain- and species-general cognitive processes—would suggest. Examples that support this contention, taken mostly from the world of casino gambling, are essentially what this newsletter is about.

Playing Blackjack for a PhD

My experience counting cards suggested a creative way to address this topic. If culture and experience is central to how people make risky and uncertain decisions even in a well-constrained gambling domain such as casino blackjack, then it would make a compelling case for their centrality in non-gambling domains where probabilities, the range of choices and outcomes, and the costs and benefits of those outcomes are largely uncertain. In other words, if the gambling metaphor is inappropriate even for understanding and evaluating gambling decisions—once real-world content and context is considered—then surely it does not apply to more removed contexts of decision-making under risk and uncertainty. I applied for grants to support field work in casinos in Las Vegas and in Prague, in large part justifying spending extensive time as a participant-observer gambling by explaining the math behind card counting that would allow me to sit at the table without losing that grant funding to the casinos. I was lucky enough—luck, of course, will play a recurring theme in future newsletters—to get two distinguished fellowships that fully funded my research for the next year and a half.1 If I had known then what I know now, I would have advised against funding anyone to spend extensive time gambling in casinos, but that’s a story for another newsletter.

The research I conducted over the next two years had three distinct methodological components. First, it was intentionally comparative; second, it involved ethnographic participant-observation (dealer school, time as a blackjack dealer, and extensive time gambling in casinos); third it used both qualitative and closed-ended interviews. Those methods are described in more detail below.

Comparative Methods

Comparisons between groups is a central feature of experimental psychology. Cognitive psychology tends to compare groups of people sampled from a single population to measure the effects of different conditions on hypothesized outcomes as a means to generalize about built-in, species general cognitive processes. Scholars studying individual differences instead sample from distinct populations based on differences in personality, demographics (e.g., gender, socio-economic status, political preference, or education), or some other measures of individual difference. Psychologists focused on expertise compare samples based on their level of experience or expertise in the domain of study. Comparison is central to cultural psychology, as well, except that the comparisons are between populations with distinct cultural histories and environments. If we want to know what makes gamblers different from non-gamblers, or blackjack players different from roulette players, or Czechs different from Americans, or experienced gamblers different from inexperienced ones, comparative methods are essential.

Comparative methods are essential for recognizing what makes people different, but they’re also necessary for making generalizations about human cross-cultural universals. One of the noted shortcomings in cognitive psychology research seeking to make generalizations about universal, inbuilt, human cognitive processes is that the research has relied on a narrow sample of participants (Arnett, 2008; Henrich et al., 2010), often first-year undergraduate psychology students fitting the same demographic as the researchers themselves, a demographic to which Henrich and colleagues creatively gave the acronym WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, Democratic), pointing to the overwhelming bias in published psychology research in that both the researchers and the participants are from countries or populations that are unrepresentatively WEIRD. Importantly, research that has tested the extent to which WEIRD findings generalize across populations has found that they rarely do, with a compelling argument to be made that the WEIRD samples are among the least representative, and in that sense not just WEIRD, but also particularly weird (Henrich et al., 2010; Henrich, 2020; though, as noted above, I suspect this result may be a methodological artifact rather than a true indicator that WEIRD people are more psychologically unique than other cultural groups).

If the premise of cultural psychology is correct that culture matters to how we think, then generalizing to gamblers as a whole or to countries as a whole rather than just to blackjack players or to the Las Vegas Strip gamblers is not solved by getting a large random sample across games or across the two countries. That would just obscure the distinctive and sometimes contrasting influence of specific games, locations, or people. Even if I just want to know about blackjack, the more comparisons, the more I can learn about what is distinctly blackjack player or gambler or American, or human, rather than due to some other characteristic that happened to be common to my blackjack sample or population. Of course, resources are always limited and comparisons are costly, but the ideal of comparison is inherent to the insights of cultural psychology.

With the above in mind, my own research was intentionally comparative in several ways:

it compared participants across different levels of experience;

it compared blackjack players with other casino gamblers (roulette and slot machines);

it compared players in distinct locations (Indiana, the Las Vegas Strip, downtown Las Vegas, and Prague, Czech Republic);

and it compared the players’ strategies with mathematical normative models that seek to maximize expected value (basic strategy and card counting).

Participant-observation

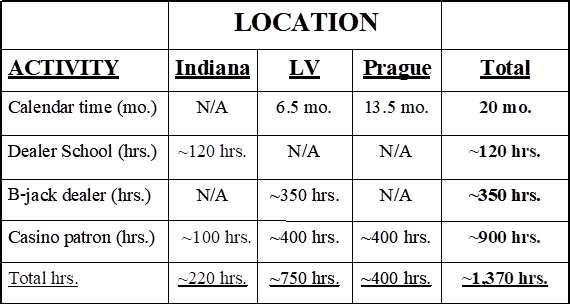

Table 1 summarizes the various participant-observation activities and the amount of time devoted to them in each of the three main locations. The activities included time in dealer school (necessary so that I would be able to work as a dealer), work as a dealer (which was not possible in the Czech Republic due to visa restrictions), and time as a casino patron in all three locations. More detailed methods can be found in the methods section of my dissertation.

Table 1. Participant-Observation Activities & Locations

Interviews

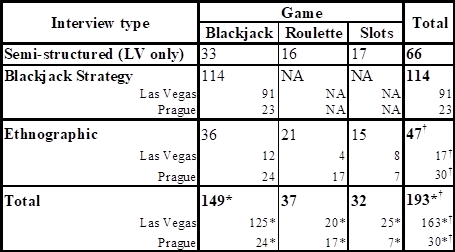

The interviews were of three types: semi-structured interviews (with a mixture of closed- and open-ended questions that could be completed in under 20 minutes), blackjack strategy surveys (that assessed players’ conceptions of basic strategy, the best way to play each hand, all other things being equal, given the player’s hand total and the dealer’s exposed card), and ethnographic interviews (recorded, open-ended interviews that usually lasted a couple of hours and allowed me to go into depth about gambling-related questions in whatever direction the interviews went). Table 2 summarizes each type of survey by game and location (again, the dissertation methods section has more details about each type of interview).

Table 2. Interview Type by Games

*-Columns do not always sum to total because in many cases the same person participated in both the blackjack strategy survey and the ethnographic interview. In these cases the total has been counted as one interview.

†-Similarly, rows do always sum to total because the same person may have participated in the same interviews for more than one game. In these cases the total has been counted as one interview.

Huge thanks to the Fulbright-Hays Doctoral Dissertation Research Abroad fellowship and the Social Science Research Council International Dissertation Research Fellowship for making my research possible!